Written by: Maya Galinsky

Hormone-disrupting chemicals are closer than you think. Yikes!!!

Understanding PFAS

PFAS are short for per and poly-fluoroalkyl substances. They are a large group of manufactured substances that are resistant to heat, water, and oil. There are thousands of PFAS chemicals and are often found in everyday products such as food paper wrapping, surface coating for carpeting and upholstery, nonstick cookware, and fire-fighting foams. PFAS can also be found in drinking water, soil, and water near landfills, manufacturing facilities, food (ex., livestock exposed to PFAS), and fertilizers. These substances, despite their widespread use, are a concern to human and animal health and the environment. PFAS are nearly indestructible once produced, easily contaminate and pass through soil, water, and air, and build up in fish and wildlife. Scientific studies suggest that exposure to PFAS in the environment are linked to harmful health effects such as reproductive effects, developmental delays, increased risk of cancer, reduced immune system, hormonal issues, and increased cholesterol (US EPA, 2021).

PFAS are actively found both in the environment and in blood samples of people (Understanding PFAS, 2020).

PFAS exposure can be found in newborns (Liu et al., 2023) and passed through breast milk (Macheka-Tendenguwo et al., 2018). Even family pets like cats and dogs have been found to harbor some PFAS at doses above the “minimum risk level recommended for humans” (Ma, Zhu, & Kannan, 2020).

PFAS and Drinking Water

Essentially there are four major sources of PFAS. These sources include fire foams used in fire training/fire response sites, industrial and manufacturing sites, landfills, and wastewater treatment plants.

What makes them so nasty is that PFAS are “forever-chemicals,” they do not break down in the environment and move through the soil, contaminating drinking water sources, and build up in fish and wildlife (Per- and Polyfluorinated Substances (PFAS) Factsheet CDC, 2021). And if needing to be cautious of drinking water wasn’t enough, one can also be exposed by breathing contaminated air (Morales-McDevitt et al., 2021)!

PFAS and Human Health

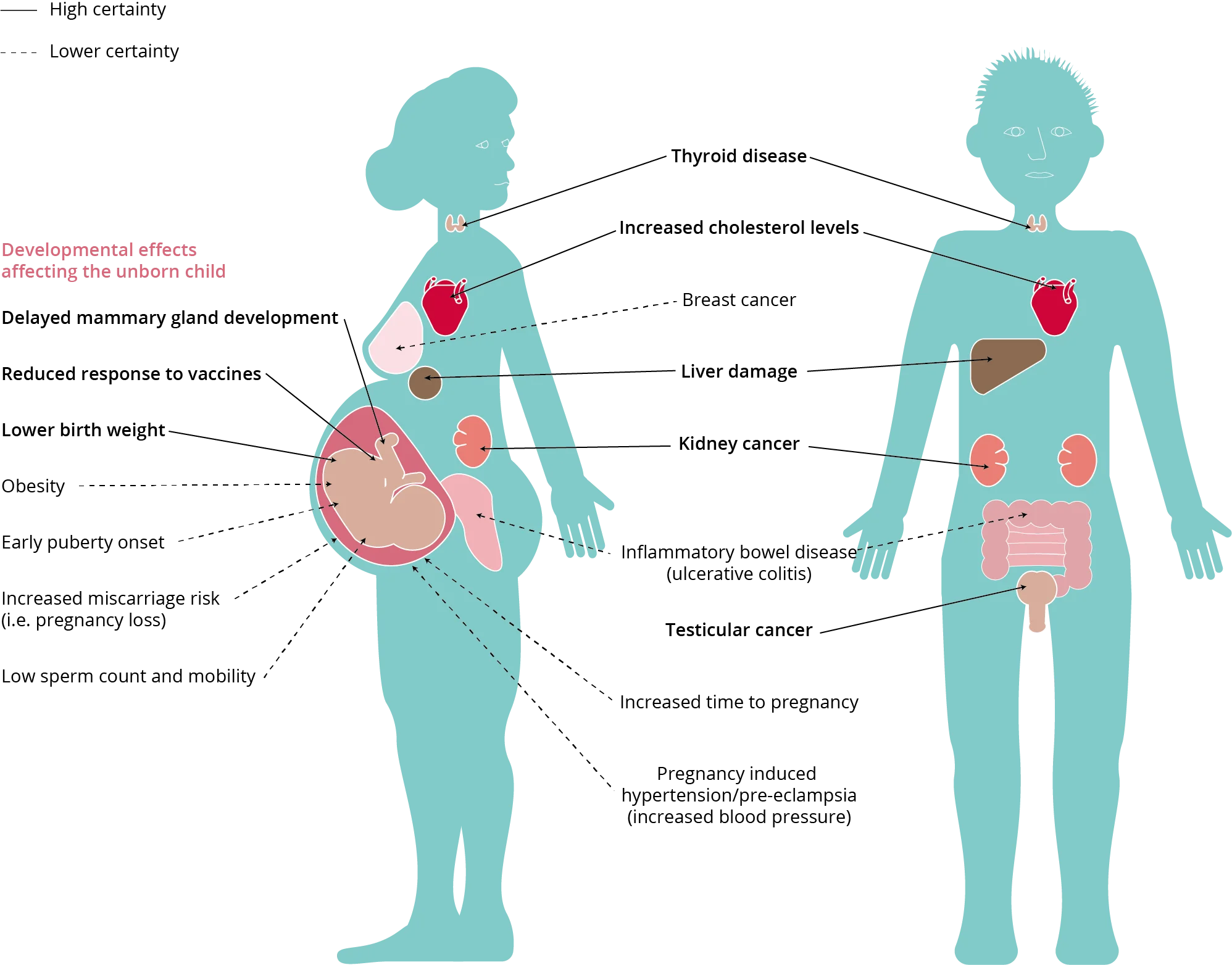

Although we don’t have sufficient data yet on low exposure risks, we do know the risks from high exposure. These include:

Increased Cholesterol levels (Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, 2020)

Decreased vaccine response in children

Effects on growth, learning, and behavior of infants and older children (Szilagyi, Avula, & Fry, 2020)

Impaired thyroid function

Impaired immune system function

Changes in liver enzymes

Increased risk of kidney or testicular cancer (Steenland & Winquist, 2021)

Metabolic diseases like obesity & diabetes (Donat-Vargas et al., 2019)

Low Sperm count and smaller penis size (Di Nisio et al., 2019)

Regarding Reproduction Among Women:

Increased risk of high blood pressure or pre-eclampsia in pregnant women

small reductions in infant birth weights

Lower chance of getting pregnant (CDC Newsroom, 2016)

Increased chance of miscarriage (Liew et al., 2020)

In short, PFAS is bad news.

Recent discovery

PFAS and Period Underwear

PFAS have been identified in period underwear. Companies advertising their period underwear as “non-toxic” and “Organic Cotton Underwear” show high indications of PFAS. Indeed levels

“high enough to suggest they were intentionally manufactured with PFAS” (Choy, 2020).

High levels of these toxins are especially present in the crotch area: specifically in the outer or inner layer. The public is aware that PFAS are harmful when ingested orally. A recent study shows that the absorption of PFAS through the skin is equally harmful (Shane et al., 2020).

Mamavation, a U.S.-based environmental wellness site investigating toxins in everyday products, sent 17 pairs of period underwear from 14 brands to an EPA-certified laboratory for fluorine testing – a standard indicator of PFAS contamination (Segedie, 2021). Their results were shocking.

About “65% of products tested had detectable levels of fluorine present.”

Eleven pairs of the 17 brands tested had detectable fluorine present. But on the bright side, six brands were utterly free of detectable fluorine. This would suggest that period underwear can be manufactured without these harmful toxins!

Menstruating people do not want toxic chemicals near the most sensitive (and absorbent!) part of their bodies. Since PFAS remains in our bodies for years to decades after exposure, it runs the risk of being passed down through child-bearing people to their future children. It is critical to actively avoid PFAS around the vaginal area (and anywhere else) since it builds up in the body.

PFAS and Tampons

PFAS has been identified in both conventional and organic tampons. The Environmental Health News (EHN), an environmental wellness blog and community, had 23 brands tested – both organic and conventional – at a certified lab and found levels of fluorine ranging from 19-28 parts per million (ppm). These detectable levels are considered to be “not intentionally added” by the manufacturer and are likely the result of contamination in the supply chain. Linda S. Birnbaum, Scientist Emeritus and Former Director of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and National Toxicology Program, responded, “we already know that PFAS has the ability to impact almost every organ of the body. The vagina is an incredibly vascular area, and dermal exposure is often higher there than in other places of the body” (EHN Staff, 2022). It is also noteworthy that PFAS represents only one of many classes of chemicals found in tampons as manufacturing by-products.

PFAS and Pads

EHN and Mamavation partnered up to detect levels of PFAS in sanitary pads, panty liners, and incontinence pads. Of 46 pads tested at a certified lab, 22 had levels ranging from 11-154 ppm. A whopping 13 of the brands detected with fluorine advertised themselves “as ‘organic,’ ‘natural,’ ‘non-toxic,’ ‘sustainable,’ or using ‘no harmful chemicals’” (EHN, 2022).

PFAS and Menstrual Cups

A key difference between menstrual cups and tampons, pads, and period underwear is that the cup collects rather than absorbs menstrual blood. Menstrual cups lessen exposure to toxic chemicals since most toxins from pads and tampons stem from the pesticides used on the cotton and manufacturing processes, such as bleaching. When buying a menstrual cup, searching for one entirely made of medical-grade silicone without dye is recommended. Make sure that the cup is free from BPA/BPA replacements and phthalates, “two hormone-disrupting chemicals that should not be inserted into the body” (Persellin, 2022).

How did this happen?

Why are brands claiming to be PFAS-free when they are not? The false claims stem from using OEKO-TEX®-Certified fabrics for the creation of the period product. OEKO-TEX® ensures that textiles have been tested against a long list of harmful substances and therefore are harmless for human health. These certified brands believe that OEKO-TEX® means “PFAS-free,” although this assumption has proven false. OEKO-TEX® tests for only the most common PFAS chemicals and does not test their fabrics for fluorine (Standard STANDARD 100 by OEKO-TEX®, 2021). Moreover, OEKO-TEX® only relates to the state of the textile after production and does not declare anything regarding contamination resulting from transportation, storage, packaging, and inadequate manipulation. Since they do not test for the following factors, they can not vouch for any of the other thousands of PFAS chemicals out there. Out of all industries, the only industry that properly tests for fluorine is the composting & food packaging industry.

U.S. Legislation

Public health policymakers are also standing up and taking a stance in the U.S..At the beginning of 2023, California mandated the disclosure of ingredients in menstrual products. The downside is that this law doesn’t include all 9,000+ chemicals in the PFAS chemical category since it focuses only on the “intentionally added” chemicals. Before California’s new law, New York was the first state to mandate the disclosure of all “intentionally added” ingredients inside all menstrual products. The common theme here is the emphasis on “intentionally added.” This wording leaves a legislative gap for PFAS and brands to sneak past their “sustainable” marketing campaigns and enter period underwear.

What can you do?

First and foremost, when choosing to invest in period underwear, shop smartly. Always choose a brand that has performed independent, 3rd party testing and is open to disclosing its results. You can also verify the product is on their certifier’s website, such as the Global Organic Textile Standard (GOTS). GOTS is recognized as the world’s leading processing standard for textiles made from organic fibers, including ecological and social criteria.

Another way to take action is to make your political voice heard and sign a petition. Two organizations that are making a change in the states include Sierra Magazine and Women’s Voices for the Earth.

Summary

Independent testing and transparency have proven themselves, again and again, to be necessary for consumer safety. Regarding personal hygiene, we must be careful and educated on what can harm our reproductive organs. The period product industry must catch up with society’s increasing awareness. Specifically, regarding period underwear brands, third-party testing is critical to maintaining customer trust. Legislation is slowly changing in the right direction, yet globally, there is much more work ahead. It is crucial for society to continue learning and spreading awareness. Every voice heard and every petition signed is prevalent in making an impact. We at Gals Bio promote transparency and open communication and commit to providing our community with full access to all available evidence-based information. Menstruators must stick together and have each other’s backs.

Reference:

Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. (2020, June 24). Potential health effects of PFAS chemicals | ATSDR. Www.atsdr.cdc.gov. https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/pfas/health-effects/index.html

CDC Newsroom. (2016, January 1). CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2019/p0923-cdc-atsdr-award-pfas-study.html#:~:text=Some%20studies%20in%20people%20have%20shown%20that%20exposure Choy (2020). My Menstrual Underwear Has Toxic Chemicals in It | Sierra Club. Www.sierraclub.org. https://www.sierraclub.org/sierra/ask-ms-green/my-menstrual-underwear-has-toxic-chemicals-it

Di Nisio, A., Sabovic, I., Valente, U., Tescari, S., Rocca, M. S., Guidolin, D., … & Foresta, C. (2019). Endocrine disruption of androgenic activity by perfluoroalkyl substances: clinical and experimental evidence. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 104(4), 1259-1271.

Donat-Vargas, C., Bergdahl, I. A., Tornevi, A., Wennberg, M., Sommar, J., Kiviranta, H., … & Åkesson, A. (2019). Perfluoroalkyl substances and risk of type II diabetes: A prospective nested case-control study. Environment international , 123, 390-398.

EHN Staff. (2022, October 27). Evidence of PFAS found in tampons — including organic brands [Review of Evidence of PFAS found in tampons — including organic brands]. EHN. https://www.ehn.org/pfas-tampons-2658510849.html

EHN (2022, December 15). Toxic PFAS Chemicals Detected in 22 Sanitary and Incontinence Pads [Review of Toxic PFAS Chemicals Detected in 22 Sanitary and Incontinence Pads]. Children’s Health Defense; The Defender. https://childrenshealthdefense.org/defender/pfas-chemicals-sanitary-incontinence-pads/

Fenton, S. E., Ducatman, A., Boobis, A., DeWitt, J. C., Lau, C., Ng, C., … & Roberts, S. M. (2021). Per‐and polyfluoroalkyl substance toxicity and human health review: Current state of knowledge and strategies for informing future research. Environmental toxicology and chemistry, 40(3), 606-630.

Liew, Z., Luo, J., Nohr, E. A., Bech, B. H., Bossi, R., Arah, O. A., & Olsen, J. (2020). Maternal plasma perfluoroalkyl substances and miscarriage: a nested case–control study in the Danish National Birth Cohort. Environmental health perspectives , 128(4), 047007.

Liu, H., Huang, Y., Pan, Y., Cheng, R., Li, X., Li, Y., … & Xu, S. (2023). Associations between per and polyfluoroalkyl ether sulfonic acids and vitamin D biomarker levels in Chinese newborns. Science of The Total Environment, 161410.

Ma, J., Zhu, H., & Kannan, K. (2020). Fecal excretion of perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances in pets from New York State, United States. Environmental Science & Technology Letters, 7(3), 135-142.

Macheka-Tendenguwo, L. R., Olowoyo, J. O., Mugivhisa, L. L., & Abafe, O. A. (2018). Per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances in human breast milk and current analytical methods. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 25, 36064-36086.

Morales-McDevitt, M. E., Becanova, J., Blum, A., Bruton, T. A., Vojta, S., Woodward, M., & Lohmann, R. (2021). The air that we breathe: Neutral and volatile PFAS in indoor air. Environmental science & technology letters, 8(10), 897-902.

Per- and Polyfluorinated Substances (PFAS) Factsheet | National Biomonitoring Program | CDC. (2021, September 2). Www.cdc.gov. https://www.cdc.gov/biomonitoring/PFAS_FactSheet.html#:~:text=The%20per%2Dand%20polyfluoroalkyl%20substances

Segedie, L. (2021, May 25). Report: 65% of Period Underwear Tested Likely Contaminated with PFAS Chemicals. MAMAVATION. https://www.mamavation.com/health/period-underwear-contaminated-pfas-chemicals.html

Shane, H. L., Baur, R., Lukomska, E., Weatherly, L., & Anderson, S. E. (2020). Immunotoxicity and allergenic potential induced by topical application of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) in a murine model. Food and Chemical Toxicology , 136, 111114.

Standard STANDARD 100 by OEKO-TEX® OEKO-TEX® -International Association for Research and Testing in the Field of Textile and Leather Ecology OEKO-TEX® -Internationale Gemeinschaft für Forschung und Prüfung auf dem Gebiet der Textil-und Lederökologie Contents Inhalt. (2021). https://www.oekotex.com/importedmedia/downloadfiles/STANDARD_100_by_OEKO-TEX_R__-_Standard_en.pdf Steenland, K., & Winquist, A. (2021). PFAS and cancer, a scoping review of the epidemiologic evidence. Environmental research, 194, 110690. Szilagyi, J. T., Avula, V., & Fry, R. C. (2020). Perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) and their effects on the placenta, pregnancy, and child development: a potential mechanistic role for placental peroxisome proliferator–activated receptors (PPARs). Current environmental health reports , 7(3), 222-230. Understanding PFAS | riversideca.gov. (2020). Riversideca.gov. https://riversideca.gov/press/understanding-pfas

US EPA. (2021, October 14). Our Current Understanding of the Human Health and Environmental Risks of PFAS. Www.epa.gov. https://www.epa.gov/pfas/our-current-understanding-human-health-and-environmental-risks-pfas